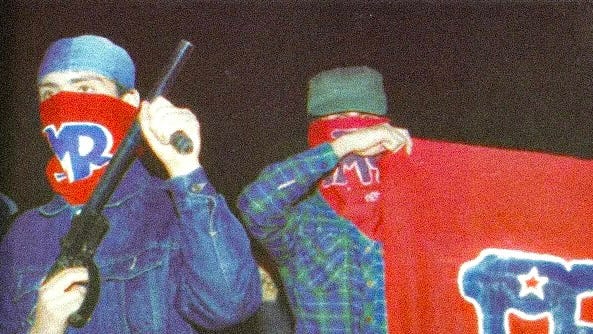

the importance of armed struggle, or the folly of the MIR & PU government in Chile, or the FPMR / DRACOS IN THE AIR

Soy así porque no le prendo una vela a dios y luego otra al diablo, pero se la prendo al tiempo.

- Salvador Gonzáles Escalona

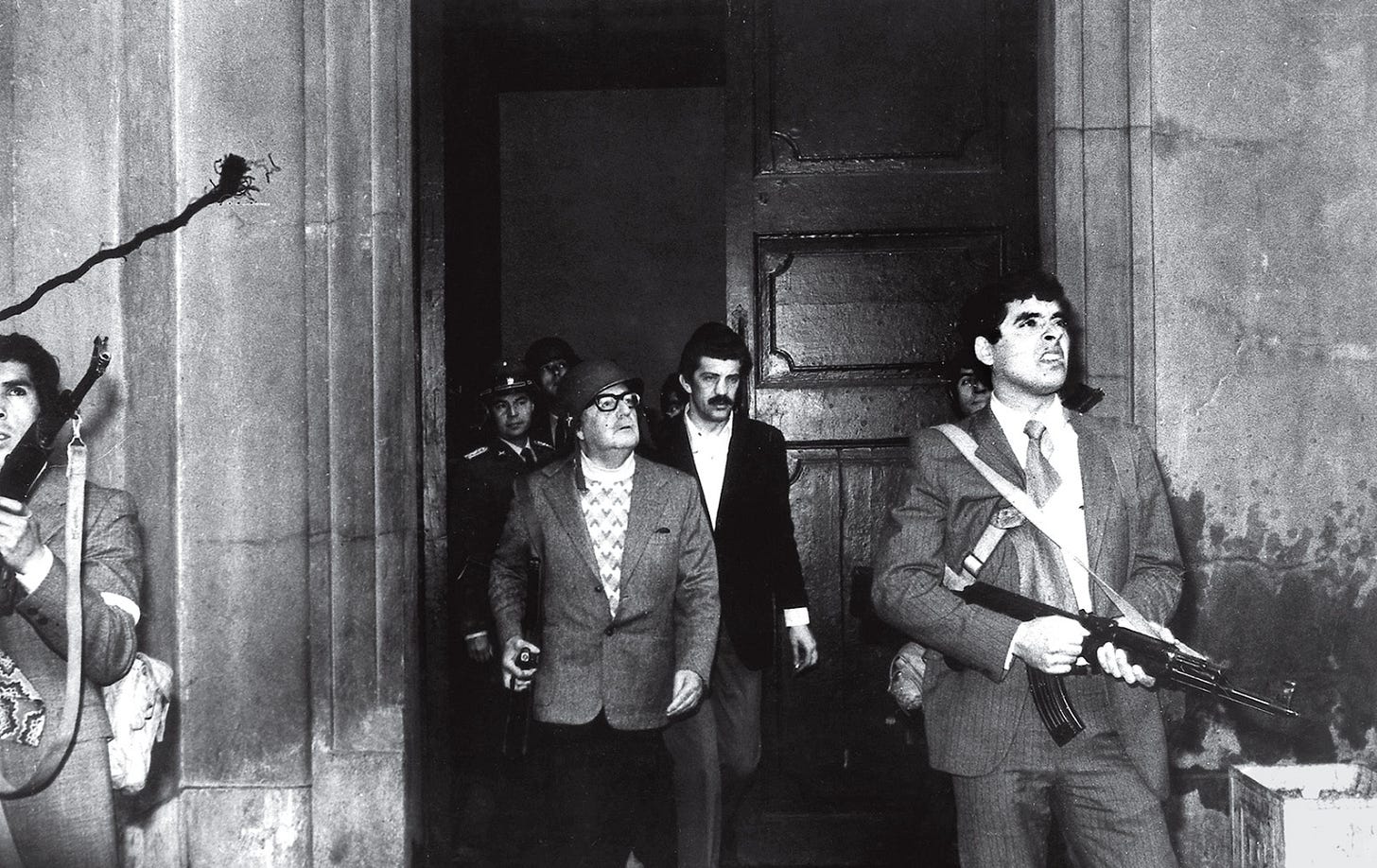

So today we’re going to talk about 9/11— the first 9/11. In Santiago, Chile in 1973, democratically elected president Salvador Allende was deposed in a Coup d'état by Army General Augusto Pinochet, Brutus-style. Allende’s core group of loyalists, along with Cuban advisors sent by Fidel Castro, suggested he go into internal exile outside of Santiago where he could regroup and lead a counter-coup against the military and carabineros (military police). In his final moments, Allende decided to stay at the palace of La Moneda (Chile’s equivalent to the so-called “White House”) while it was under bombardment by the treasonous air force and army. However, Allende’s fate had been sealed long before the morning of the coup; it was sealed even before Pinochet was chosen as the replacement for the disgraced general Carlos Prats.

On that morning, Allende was woken by advisors telling him the coup had started and that the head of the Navy had already seized Valparaiso. He and members of his praetorian guard, the GAP (Grupo de Amigos Personales), left for La Moneda in a caravan of modified Fiat 125s. The GAP was a group of Socialist partisans who were loyal to the president above all. Some of them received Commando training in Cuba, courtesy of Castro, and a small band took their Cuban-supplied AK-47s to make a stand at the palace to confront the army infantrymen attacking the building. In total, there were 40 GAP members, a number that had already shrunk by 10 following an attack in June. Of those 40, only 24 members managed to rendezvous at the palace, while another 10 attempted to enter but were arrested by the PDI (Investigations Police of Chile).

Allende tried to set a plan in motion, using the GAP to clear the high-rises surrounding La Moneda. This would secure a safe passage for the president and his loyalists to take the State Bank building, where they would hopefully give time for the Popular Unity government allies to regroup. At the time, Allende believed the state bank building was the most secure location within the capital. This plan was to be coordinated with the MIR (Movimiento Izquierda Revolucionaria). By the time Allende had decided on this course of action, the army had already moved its tanks into position and had surrounded the palace. Upon hearing a communique from Allende, the MIR retorted that they would not join the battle, given their numbers were few compared to the combined forces of the Army, Carabineros, and the police agencies.

The MIR had recently been excised from the GAP following internal turmoil over the past few months. Despite holding different theoretical beliefs from Allende and his group, they were entrusted with 250 rifles, machine guns, and communication devices to help lead a popular resistance in the event of a coup. Although MIR leadership refused to fight on the day of the coup, this was largely due to being out-gunned and strategically outmaneuvered in every way. Not only were their weapons few, but the coup had caught the leadership by surprise, and they scrambled at the last minute in factories to try to coordinate a regrouping with the militant wing of the Socialist Party (they failed). Miguel Enriquez, the group’s leader at the time, sent a communique to Allende’s daughter at La Moneda to try to get Allende to flee the palace and regroup with another MIR column. Allende rejected the offer, vowing not to leave office and handing the reins to Enriquez.

Allende failed to get in touch with his former generals for the first hour he was at La Moneda, broadcasting through the only radio station that wasn’t seized by Pinochet forces, Radio Magallens, operated by the Chilean Communist Party. When he finally got through to Pinochet, he refused to capitulate, resulting in an aerial bombardment of the Palace. Following the constant bombing by the army and air force, Allende gave one final speech to the country before he shot himself in his office with the rifle gifted to him by Castro. The surrounding GAP forces were scattered- some of them had concealed their weapons and posed as workers in a nearby building where they were posted as snipers.

POPULAR UNITY - NO TO CIVIL WAR AT ALL COSTS

The fact that Allende was so adamant about refusing to launch an armed resistance movement in any capacity, even as the bombs rained on his presidential palace, tells us everything about the failure of the Popular Unity government. The PU was primarily composed of the Socialist Party and the Communist Party, with other groups, the Social Democrats and MAPU, playing a smaller role. From the moment this alliance took power, armed movements such as the MIR and other guerrilla groups halted their direct actions, reappropriations, and violent campaigns in solidarity with the government.

The PU sought to maintain the popular support of laborers and the Chilean middle class by neutralizing its most radical proponents. While the government had little legislative power due to the opposition’s control, the agrarian and economic reform policies could have benefited from armed workers’ cadres seizing land (which some did) and counteracting CIA and big business-backed strike efforts (the Truck drivers’ strike). The sons of apes and pigs would have had no choice but to capitulate to nationalize industry. Intelligence operatives and the reactionary opposition would have had no one to cooperate with if Augustin Edwards, owner of El Mercurio, and his group of ghouls had been arrested.

Instead, the PU attempted to hold the revolution together by trying to win the favor of the armed forces. Many in the Socialist Party believed that there was sufficient support within the army to prevent a coup d'état. Even some in the MIR thought this was possible, given the popular support of the Unity government. Believing that the military was in their pocket, the PU did not support any outside militias, except for minor lip service to the MIR and unions’ CIs.

There is a tragic irony in seeing how incredibly ill-prepared the left was in this instance, given that the dictatorship published its unscrupulous Whitepaper to try to convince the world otherwise. In this so-called “Whitepaper”, Pinochet’s government outlines a coordinated plan by leftists to seize power. The document also falsely claims that there were thousands of arms smuggled into the country and in the hands of guerrillas (don’t threaten me with a good time!) and hundreds of thousands of trained insurgents at the beck and call of the PU. The real numbers were closer to 1,500 militants who barely knew how to operate rifles. This estimate includes the combined forces of the MIR, the Socialists, and the smaller ultra-left groups.

Allende and the PU had failed to realize that a Civil War was already at hand. They, along with the Chilean people, paid the ultimate price for this. Carlos Altamirano, a former member of the Socialist Party, has since recognized this folly:

"I maintain that, fundamentally, the great void, the great error of our government and the experience of the PU was having attempted to carry out a 'revolution' without weapons. An unarmed revolution."

TOO LATE TO REGROUP

The MIR was founded in August 1965 in Santiago. The group was an eclectic mix of militants from different parties, splinter parties, and splintered militant groups within those parties. Included in this original iteration of the group were Marxist-Leninists, Anarcho-Syndicalists, Libertarian Anarchists, Socialist Union Leaders, and, of course, the Trotskyists. The largest of which was a group led by Miguel Enriquez, which had splintered from the Socialist Party and had militarized into a small cell.

Throughout the late 60s, the MIR was a united front of ultras striving for revolution by insurrectionary means. Reapproprations ensued, as well as the kidnapping of a reporter, which caused the group to splinter, leaving the Trotskyists and anarchists out of the fold and Miguel Rodriguez at the head of the organization as its General Secretary.

When Allende came to power, the MIR stopped all militant action. Instead of implementing a strategically antagonistic role against the PU government, the MIR became subordinate to it. In fairness, the political miscalculation was sincere in its strategic support for the left-wing factions of the PU. It is also important to note that the MIR recognized the popularity of the PU government, and any movement against them would be seen as treacherous and cannibalistic by the majority of left-supporting Chileans. Instead, the group postured to uplift elements in the PU that they saw as their natural allies while trying their best to stymie the phantoms of the bourgeois/liberal parties.

Herein lies the group’s greatest miscalculation: their view that by appeasing the Allende government, they could bring themselves to power via intrigue and incrementalism. By abandoning their militarism and incorporating their forces into the popular government, they believed that cooperation would be the simplest route to a dictatorship of the proletariat.

When the coup, along with its repression, came, the MIR and its small cadres were insufficient in their resistance both in arms and in their influence on workers’ militias. The armed forces made quick work of the leadership, and the rest were forced to go underground. It took only one year for the general secretary to fall and for its organization's structure to fracture. When the militant wing of the revolution is sparsely armed, asymmetric warfare is essential. The MIR did not even have the capacity for asymmetric warfare, as was made evident by the leadership and the events that took place during the coup.

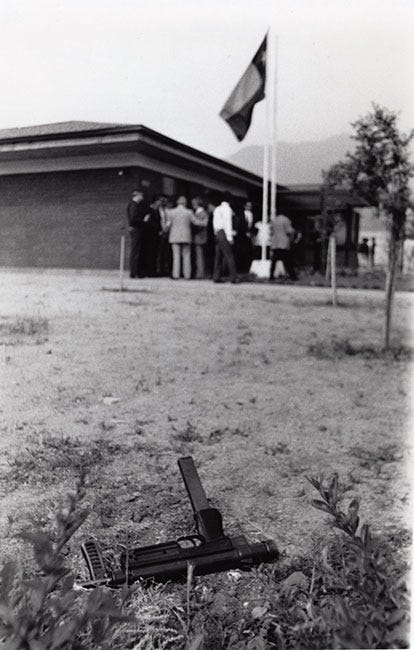

That day, September 11th, there were skirmishes along the southern parts of the city. MIR, the armed wing of the Socialist and Communist Parties, along with 200 workers, attempted to regroup. Miguel Enriquez decided to stay out of the fight, needing a few hours to organize and dig out their weapons, since most had been buried a few days earlier. The communists were squeamish and failed to take any decisive action. The group was still waiting for a response from a phantom left-wing cell inside the armed forces. (We know now this would-be group of loyalists within the army failed to materialize; this is in part due to the lack of organizational structure, but also on the same day, the coup plotters gave specific orders to shoot any hesitant officers.) The military then routed the meeting of left-wing leaders during their deliberations. A small contingent of militants then made a break for the Sumar Nylon textile factory in the neighborhood of La Legua. Here, socialist party militants, a ragtag group of communists and factory workers, decided to make a stand. Having distributed arms, the group spread out into small bands that took to the streets to confront the usurpers.

Roughly 300 men dispersed through the neighborhood of La Legua, doing their best to confront the black hand of history that was upon them and to impart the world with a collective memory of their struggle. A group of comrades decided to use a water tower at the facility as a lookout post. After spotting a military helicopter, the guerrillas began relentlessly firing at it, forcing its retreat. It is these small acts of valor that are still embedded in the memory of the neighborhood; the history of the struggle has been passed on to the next generation.

One account by militant worker Jose Moya illustrates the desperate nature of these initial skirmishes:

“We spent the whole night waiting for weapons that never arrived. We heard gunfire along the San Joaquín Belt, where there were several companies; at least one of them had weapons, a textile company, Sumar [...] Our hopes were that weapons could arrive at any moment, and we could do the same. But nothing materialized.”

There are dozens of accounts from workers, union leaders, and party members, all expressing similar sentiments. Failing to make any political gains or military concessions with the PU ultimately led all the armed leftist groups towards a dead end, which meant the death of armed resistance in Chile. They did not have the weapons of the Sandinistas or the logistical structure of the Tupamaros; the Soviets were not ready to support an armed struggle because Allende opposed it from the start.

From Valparaiso to Santiago, the military had seized control of all industrial infrastructure, captured party members and union leaders, and tortured, raped, and eventually murdered them. Most of their bodies were disposed of in undisclosed locations, never to be seen or heard from again. This is, after all, where the term “the disappeared” was first used in the context of Latin America. We see similar fascist methods now being used by so-called “drug cartels” (CIA assets) in Mexico. But that is for another day.

Throughout the first two days of the coup, the majority of leftist militants were gunned down. Some were captured and tortured for information on their comrades, others were executed, their corpses thrown over the Bulnes bridge so their bodies would float along the Mapocho river. This inhumane tactic of psychological warfare was used to intimidate the citizenry of Santiago.

He's drilling thru the Spiritus Sanctus tonight

Through the dark hip falls screaming, Oh you mambos

Kill me and kill me and kill me- Scott Walker

People were “disappeared” daily. The National Stadium was converted into a concentration camp for dissidents. Popular folk singer Victor Jara was famously tortured and then executed by firing squad at the stadium. Jara’s body was then dumped by a patch of bushes near the Metropolitan Cemetery, where locals later found him. His wife identified his body at the morgue, where she discovered his hands had been broken by rifle butts and his body riddled with 44 bullet wounds. She later claimed that a newspaper had reported on his death as “non-violent.”

Right-leaning publications openly advocated for citizens to snitch on their neighbors for committing thought-crimes. Rightists were even offered a bounty for every dissident they turned in, along with any money the suspect currently had on their person. A hit list was published by CIA-funded newspaper El Mercurio denouncing the so-called “domestic terrorists” and persons of interest, most from leftist organizations. El Mercurio’s treachery shows us how little faith one should have in the so-called “fourth estate”, especially in an age where media outlets have been seized by conglomerates, billionaires, and quasi-state-sponsored organizations. Many of the media outlets in Chile at the time downplayed the political repression and mass-killing campaigns. Some reporters were even in league with the death squads of the DINA. Those who dissented and attempted to conduct political investigations were killed.

In 2006, years after the fall of the dictatorship, the Valech Commission on torture was launched at the behest of President Ricardo Lagos. They concluded that over 38,000 people were subject to kidnapping and torture by the military Junta. The commission also interviewed some 3,339 women, most of whom say they were interrogated and subjected to sexual violence while they were imprisoned. Hundreds of these same women admitted to being raped by military personnel and government agents. These cases involved electrocution, genital mutilation, rape in front of family members, and other sadistic methods that have been recounted thousands of times by survivors, many of whom are still seeking reparations and accountability through the judicial system.

DRACOS IN THE AIR

After a decade of repression, most leftist cells had gone underground. Miguel Enriquez was killed a year into the dictatorship by DINA (Chilean CIA) agents after they had located a vehicle used in a supposed bank robbery. The agents recognized one of the passengers in the car as Humberto Sotomayor, a MIR operative. There was an exchange of fire between the two vehicles, but the MIR managed to juke the agents and make an escape. They retreated to a safehouse but were once again discovered by the agents. Upon spotting them outside, the MIR began to fire at them. After an exchange of fire, Sotomayor and two other insurgents were able to flee from the house to safety while Miguel Enriquez came out bearing an AK-47. He was shot dead by the agents after another brief exchange of fire with them. DINA later claimed that they also located stolen banknotes from the Bank of Chile robbery once they had cleared the home.

According to a CIA report, these claims were more than a little dubious:

“Following the shooting, DINA personnel sealed off the

house, to date, despite protests from within the ministry of

defense, DINA has not allowed any other intelligence service to

examine the documents and material confiscated, in addition, DINA

maintained that the MIR was responsible for the bank of chile

robbery and that 15 million escudos found in Enriquez' house

was part of the 37 million stolen from the bank, carabinero

officers and officials of the department of investigations (DIS),

however, disputed the DINA contention, they maintained that

the mode of operation was not that of the MIR, which uses

military caliber weapons, masks and gloves. DI officials

compiled the names and locations of all known bank robbers, who

had committed crimes in the style of the bank of chile robbery.

Among them was Nelson Aramburu Soto, who was arrested

and subsequently confessed to the robbery.”

It was typical then, as it is now, for agents of the state to plant false charges on its many dissidents. We have seen time and time again the use of false evidence being planted in an attempt to discredit opposition forces. It was small incidents like this widely reported in the right-wing media that helped turn a lot of the public against the armed struggle during the first decade of the dictatorship.

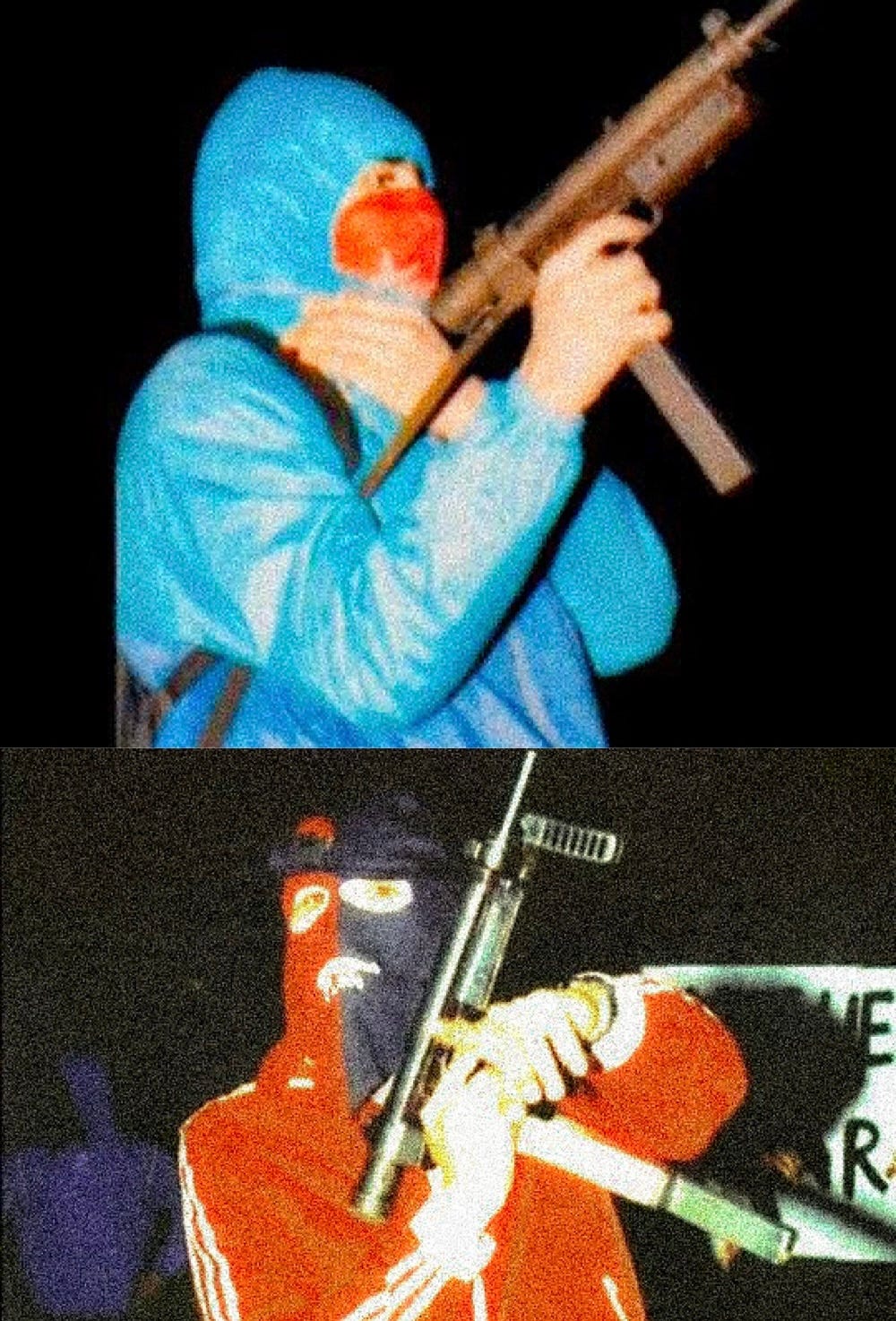

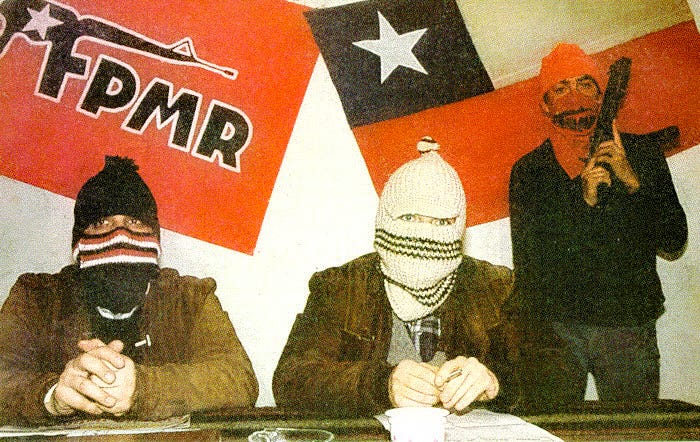

In 1984, with the help of the USSR, Cuba, and Chilean Socialists in exile, the FPMR (Manuel Rodriguez Patriotic Front) was formed as the militant wing of the Socialist Party. They announced themselves to the world by sabotaging electric towers throughout Santiago.

The organization did the best they could with what little they had. As discussed previously, leftist groups had few arms, and most of the members of these militant factions were untrained University students. The head of the movement, known by his nom de guerre, Comandante Jose Miguel, was a Chilean Socialist who had returned from exile after receiving military training in Cuba and then fighting alongside the Sandinistas in Nicaragua.

The FPMR is known primarily for a valiant assassination attempt against Pinochet. The group had managed to smuggle in weapons from Cuba (although DINA agents intercepted their larger cache of small arms), which they used to arm their cell of militants and conduct the attack. After the botched assassination of Pinochet, which ended up killing several guards and only moderately wounding the dictator, the group fractured. Different factions split from the Socialist Party, while others continued the struggle as an autonomous group. The party apparatus soon fell apart with the death of its leader, Commandante Jose Miguel. He and fellow Commandante Tamara were captured and tortured in the south of Chile after attempting to start a Foco-style people’s war in the rural O’Higgins region. Their bodies were later found floating in the Tinguiririca River.

What the FPMR signaled to the nation-state of Chile was its growing fragility. Held together for 15 years by media censorship, police-state violence, and a U.S. vision for a neoliberal economic system, the country was exhausted, and its social fabric was becoming a powder keg. This is evident in the large social movements and demonstrations that rocked Chile during the time the FPMR was most active in the 1980s. The ratcheting up of violence had become the dying flails of a fascism that could not contend with itself.

Although their main objective failed, Pinochet was deposed via a referendum that gave the Junta immunity. The group instilled in the Chilean populace a sense of dignity and a small but capable front that was willing to risk everything to end the dictatorship. The memory of the FPMR still lives on in Chile, and the left, which was mocked for so many years, has reemerged both at the party level and that of a popular movement, which has become increasingly more bold in its forms of resistance. The new breed is here, armed with the collective memory of their people.

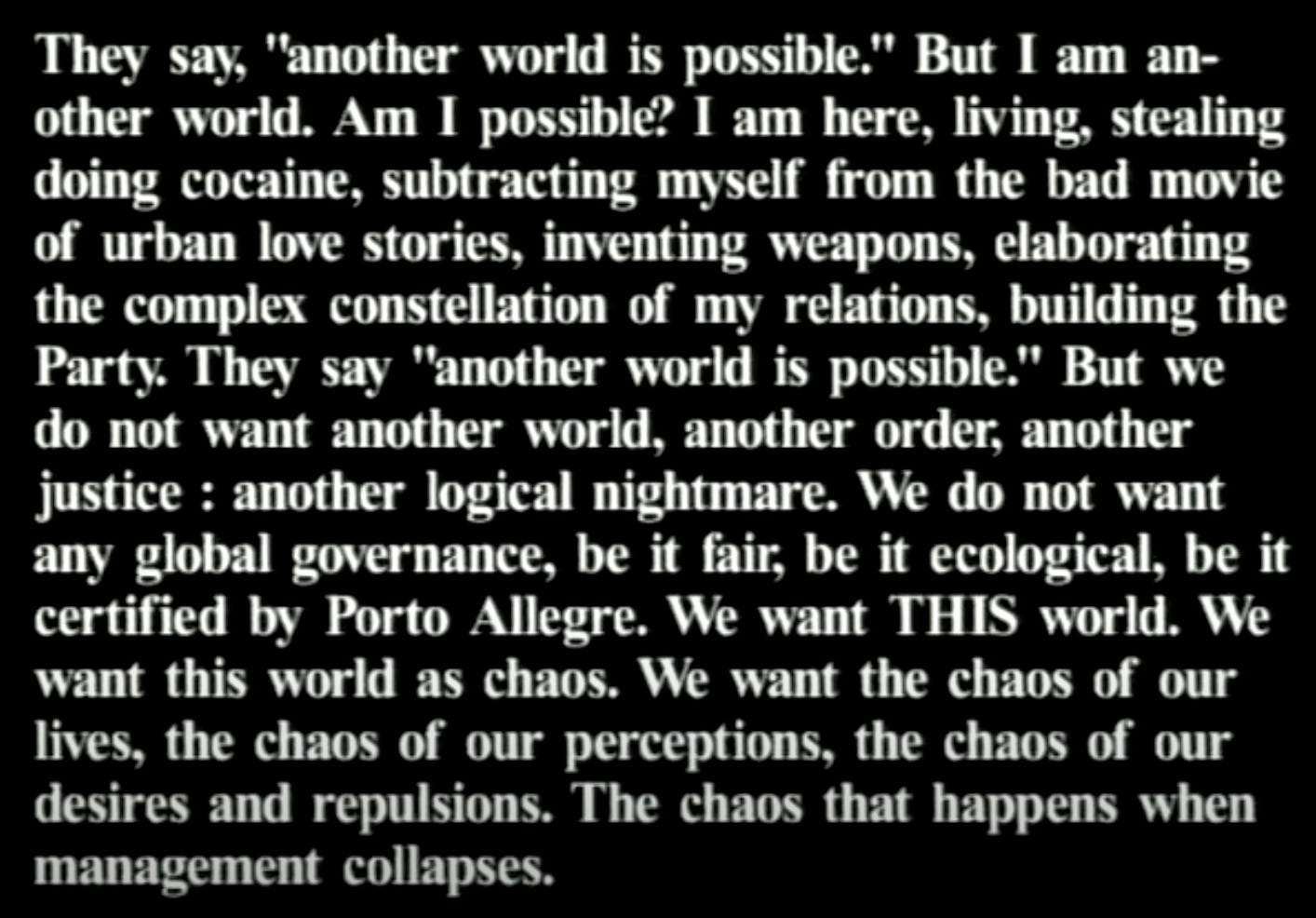

Currently, the Chilean right is divided, and despite floundering a bit in the polls and the lackluster governance of Boric, the left may have a repeat of the 1970s. The conditions are there for Jeannette Jara to take the presidency. The real question we must ask is, are the insurgent-ultras of the new generation ready to face the coming right-wing assault? While Chile and its politics are on the periphery of most states, Marco Rubio’s gaze extends to all of Latin America. As of writing this, the U.S. state department has sent 4,000 marines off the coast of Venezuela as a show of force to Nicholas Maduro and his “Narco Government”. At the same time, we have heard reports of NORTHCOM readying special operators to conduct raids in Mexico against the so-called “cartels” that the CIA arms, trains, and regulates. In Chiapas, the Zapatistas have warned of a civil war looming between local militia groups, cartels, and the government. They have not yet realized that the Civil War is already here.

Those who still cling to the reformism/incrementalism of the PCC must prepare themselves for the reactionary forces to come. As for the liberals, they will cooperate with any rightist party; let us call their pacifist ideas for what they really are: woefully unserious. To Kaiser and the libertarian party in favor of decreasing gun restrictions, we say open the floodgates. The people will choose sides accordingly.

the communiques have gone silent

100 FPVs soar over Roatan, spirals of doom’s halation over the sea

the moment has been secured, usurped from Emperor Time

first their villas, then their offices

you can hear the clank of machinery

the slog of Cossacks up on the hills

strange crosses sewn on their triceps

the inevitability of stochastic motion,

when the hum quantifies you

tears thought asunder

and the eyes explode on the tilled path

before freedom

those who destroy the present will have redeemed the past

“…his glance no longer shrivels me up nor freezes me, and his voice no longer turns me into stone. I am no longer on tenterhooks in his presence; in fact, I don't give a damn for him. Not only does his presence no longer trouble me, but I am already preparing such efficient ambushes for him that soon there will be no way out but that of flight.”

- Frantz Fanon